Looks like we might have movement on the water front. Severn Trent are coming out, possibly Wednesday, to repair the leak in pipe between us and the mains. Fingers crossed. That’ll be an absolutely huge weight off my mind. You can clear hear the leak from inside the house now and it’s getting louder – the sound of running water constantly is not pleasant when you know it’s basically going out of the pipe and in to the ground!

Memories are made of this

I don’t remember life events very well. When they happened, what year, where I was, or in many cases, that they happened at all. Reading back over blog entries really helps. So I’m going to try and keep writing them. I never thought actually keeping a diary would be useful, but I guess it would have been given how bad my memory appears to be for this kind of thing. I can probably recall the command line parameters for AIX commands from 1998, but not much about my life in that year (except obviously, I got married).

Fizz is back home. She was in the vet’s for one night, and was much brighter the next day. She didn’t really eat while she was there (and judging by the poo this morning, she didn’t shit while she was there either), but they felt that was more because she was stressed and unhappy with them, rather than unwell. So we agreed we’d bring her home. She’s mildly anaemic, and seems to have sporadic bouts of sickness which trigger the lethargy. So we’ve agreed to manage symptoms rather than put her through multiple tests which might not help anyway. She’s 16, and overall she’s happier and more active these days than she was a year or so ago (we’ve introduced an anti-inflammatory for her arthritis, and a laxative to help with ‘regular movements’, both of which have had a visible and positive effect on her behaviour). We’ll keep an eye on her, and manage any symptoms and ensure she’s got the best quality of life possible for however long she keeps going. At the moment, we’ve got no reason to doubt that could be a lot of years yet.

No progress on the mains leak, Severn Trent haven’t been back in touch and we don’t know what that means.

No progress on the wood repairs, the guy is waiting for a dry day to come and do the final sanding and staining.

I’m three or four weeks in to a new photography project, documenting the area in which I live. You can see the album of hundreds of photos so far on Flickr.

Dear Diary

Over two years since I last blogged anything. So long in fact that WordPress is completely different. There’s some kind of weird block editor that I don’t understand. Why can’t I just write text in a huge box like I used to?

Aha, installed a plugin to turn that off, and back to normal simple text input in a dialog box. I guess they think people will only blog tiny missives these days, but I’m here for the epic long hall and the block editor does not suit!

This will be a rambling blog post with compressed and confused timelines, missing information, out of sync actions, and no conclusion. You’re welcome.

There are always grades of discomfort, I think I might have blogged that before, and my life is easy compared to very many people in the world. I don’t think I really understood privilege when I was blogging a lot a few years ago, but over the last couple of years or so I’ve come to understand it a lot better. So I’m privileged, but as should be obvious, it doesn’t mean that shit doesn’t cause anxiety. And so September, October and now November are the months that just keep on giving. I’m blogging because I want to rant partly about work, and that means I can’t use Facebook (too many work colleagues), and I can’t use Twitter (240 characters). So I need somewhere I can vent sure in the knowledge no one will ever read it, and so my personal blog seems like the perfect choice. This is not going to be one of those posts where I focus on 3 good things and how lucky I am. That’s never the person I’ve been. I can’t fight against it really, I’ve always looked at the problems and thought about the issues, and that includes my own life. It’s what made me excellent at my job in technical support, but it comes with a burden that it’s hard to see the good things amongst the broken.

I am, as anyone who’s read this blog will know, terrible at owning a house. The last few months have tested that to the limit and continue to do so. We noticed some woodlice in the corner of the dining room, we knew what it was, rotten wood, we just weren’t sure why. But dealing with that takes energy, and the last three months have been low energy periods for us for several reasons. So we didn’t deal with it straight away, and then it started preying on our minds, making it harder to sleep, consuming more spoons, adding more to the cup, whatever metaphor you prefer. Eventually, Greté found enough energy to contact a handyman on Facebook, and it’s being handled. Never as bad as you fear, but never as easy as you hope. It’s half fixed, but now we’re waiting for some dry weather for the guy to finish the job (for which he’s already been paid).

There’s also a leak in our mains water supply. A good few weeks back now we noticed that the cold water pipes were making a noise as if someone was running a tap. Initially, I didn’t think much of it, but then I began to think about what it might imply before finally realising it probably meant a leak. At first, I assumed it was in the house, and so I spent 3 hours one night, until 2am, because when else do you panic about this stuff than at 11pm before you go to bed, trying to find it. There wasn’t anywhere in the house that obviously had any water leak. I formed the view the leak was outside. What followed was is rather frustrating. We had a British Gas appointment to check the boiler anyway, and they provide plumbing repairs and quotes, so we asked them to also ‘check the plumbing’. The guy who arrived thought he was only here to find a plumbing issue, Greté managed to get him to do the boiler service, and he agreed he thought the leak sounded like it was outside in the mains pipe. He had another guy come the next day, from Dynorod (who I think British Gas own) to confirm that, and he did. There was some confusion that included being told if we signed up to the extended home care agreement it would cover the problem. So we signed up. We them had an appointment scheduled for many weeks later for Dynorod to come and ‘find the leak’. However, before that occurred, Dynorod called us to say it wouldn’t be covered because the cover only covered internal pipes. Many furious conversations later didn’t provide any progress. I then called our insurance company, but their ’emergency cover’ line told me because I’d already had a plumber look at it, they wouldn’t cover it, even though they literally just listened to a pipe. Our regular buildings insurance doesn’t cover it (most likely) because it’s wear and tear. But they advised us to ring Severn Trent first anyway, which we did. About three weeks had passed now, with the sound of water leaking in to the ground present in the house all the time. We also asked Dynorod to come and quote in case we needed them to do the repair. A lovely lady at Dynorod rang us the day they were supposed to be here, to tell us they were running late and to berate us for getting them back when they said it wouldn’t be free. I explained we were getting them back to quote, and that if they didn’t arrive soon we’d have to go out. She told me she could quote and we never needed them to visit anyway, at which point I was pretty pissed off. So, anything from £700 to £2000 depending on where the leak is, but that’s open ended if access proves hard. Meanwhile, Severn Trent have now been twice, once to confirm it’s a leak (sounds like it), and once to put a boundary box outside the property, and a meter to measure the rate of loss. Now however, upon ringing them today, they’re not sure what’s happened, who we may or may not be passed to, and what the status is. So several weeks after first hearing the noise, we can still hear it, and there’s water leaking in to the ground somewhere between us and the mains. It’s like water torture for real.

In Tesco car park, sometime in the last two months or so, it’s a blur, I was slowly reversing out of a parking bay when someone drove in to the back corner of the car. Their passenger side front corner impacted my passenger side rear corner. The insurance company didn’t even bother debating it, I was reversing so my fault. I would maintain I checked, it was clear, I reversed slowly, and someone travelling too quickly drove in to the car. However, I’m now £300 worse off (excess) and we’ll see what it does to the premium. First insurance accident claim we’ve ever made, since Greté started driving in 1997ish. Not a big deal, but I’ve never had to deal with car insurance companies, and my natural ‘must follow the rules to the letter’ behaviour gets in the way when those rules are fucking unclear and contradictory. Just another spoon theft I don’t need.

Fizz has been unwell for a few months now. She had full on heart failure a while back and we got to her to the vets and essentially saved her life. Since then, we’ve been extra vigilant, as you might imagine, and are managing her thyroid issue, and several other conditions. Over the past month though she’s had another serious health scare, and a couple of periods of extreme lethargy, including yesterday. We felt we might lose her overnight, but this morning she seemed brighter. We took her to the vets at 6pm today though, to be safe, and they’ve kept her in overnight for more tests. She may be anaemic which has many possible causes. She’s 16, and we’ll need to think carefully about how we manage her quality of life in the face of any new challenges.

Work is bitter-sweet. There’s some good news coming for me personally, a new challenge, new opportunity, but it’s amid a complex, ego-driven, murky, cost-saving-focussed organisational battle. People are burning out, and being burned out. I look around and wonder if this is what failing organisations look like, but we refuse to believe it. Or maybe I’m just more exposed to it now that I have an increased level of involvement in senior management. Who knows. I still manage to leave it behind when I get home, for the most part, which is a bonus over the job I had before, and some days it’s so terrible it’s truly funny and easy to rise above. But I hate when people suffer, and I see a lot of suffering, and some days it saps energy I need to use to be taking care of Greté and the shit above. When work consumes too many spoons, the balance is broken.

Greté continues to suffer at the hands of the DSS, in parallel to suffering at the hands of her health issues, one of which is literally suffering of her hands. Around this time last year we got the regular invite to fill in the WCA form, which we duly did, and we waited. We got an appointment in January for the face to face assessment, and then last minute it was cancelled. Apparently, they didn’t have ‘anyone with the specialist skill required to assess her’. Okay, at least they were honest. We waited for a new appointment. And waited. And waited. And finally in September, we received this,

Your appointment at 2.45pm on Thursday 17th JANUARY has been rescheduled for Monday 16th of SEPTEMBER

Literally nine months. Greté called them on the Friday before to ensure the recording equipment was available as instructed, to be told that it was being rescheduled because they’d got the booking wrong and hadn’t lined up a doctor. For. Fucks. Sake. They moved it to October 8th, making it nearer to ten months since the original invite and pretty much 11 months since we’d filled in the original WCA. In that eleven months, Greté’s health has gotten worse, and medication has changed, and and and …

Anyway, we attended, the assessment went ahead, the audio recording equipment (actual C90 tapes) failed just over half way through but we got through it. Ultimately, on October 24th Greté received the notice that she’d been placed (kept) in the ESA Support Group. That’s the group that means you do not need to seek employment to continue receiving the ‘benefit’. No indication of when that will be reviewed next, when we have to start that whole dehumanising process all over again, but it’s done for now.

Tragically, we won’t soon forget the date Greté got that news (which is bitter-sweet in and of itself). It was also the day we found out that our dear friend, Lynda, had passed away overnight.

We’ve known Lynda for a long time, and I’ll keep personal details out of this entirely to maintain her dignity. She lived with and in-spite of multiple serious medical conditions, she gave no quarter, she smiled and never stopped. She didn’t fight her illness, nor lose to it, she rose above it in life knowing the inevitable conclusion. We will miss her forever.

None of these issues individually are unmanageable. Some are tragic and heart breaking, some are annoying, some are frustrating. But at the same time, grouped together, with some of them being a constant nagging worry / fear, sapping energy and spoons, they’re impacting both mine and Greté’s mental health in ways neither of us need.

We’ll be okay, we’ll get through. I have a good credit rating, there’s equity in the property, the vets are looking after Fizz, and we’ll be able to handle anything which transpires, but fuck me it feels hard sometimes.

Mass Effect (again again)

A friend of mine has been discovering Dragon Age and then Mass Effect for the first time. It’s been pleasing to see how much he’s enjoyed all the games, even though some of them are pretty long in the tooth these days.

It also inspired me to go and play Mass Effect 1, 2 and 3 again (I’m about 10% through ME3).

It’s a bit depressing how badly Andromeda stands up to Mass Effect (certainly 3) in terms of story and emotional engagement. The side stories in Mass Effect 3, the overheard conversations, are heart achingly tragic and poignant. And they’re not even part of the overall story, you can’t even always influence them. There’s a elderly lady in one location trying to contact her son, who’s in the military. You don’t know if her son is okay or not, but you know she’s got memory issues, because she’s confused and doesn’t realising she’s been having the same conversation for several days. You get the conversation in snippets, and the response from the woman she’s speaking to is so real. There are loads of conversations like that, moments, ‘real’ lives, telling a story of people affected by war.

Andromeda tried, but it missed, and I guess while it’s mechanically a good game, it just doesn’t have the heart present in ME3 (BioWare have form here, DA2 didn’t have the same heart as DA1).

Anyway, just a short post in passing – Mass Effect, the whole trilogy, is still worth buying and playing if you’ve never done so.

Diabetes

I was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in 2005. In the 12 years since we found the right level of medication, the metformin dose I’m on has never changed. Until today. Up from 1500mg a day to 2000mg a day, with a promise from me to the GP to also lose some weight with my intent being to reduce that dose again.

Ever since the accident last year, and to be fair, for a short while before it, my sugar has been creeping up and my HbA1c’s getting worse. I’ve had a couple of ‘soft’ attempts at getting it back under control, but not enough to offset the changes, and so it’s time for a bit of focus. I don’t want the change to be permanent, I want to be able to reverse it, and I’m going to try hard and delay the ‘inevitable’ slide towards insulin for as long as possible.

It remains to be seen whether my will power will be strong enough to actually lose weight, but I’m going to give it a shot.

I’m pleased the GP was once again willing to work with me, rather than simply sticking me on a new medication or insisting the change was larger and permanent.

Interesting, the only reason I know it was 2005 when I was diagnosed, is because I read back and found the blog posts where I started talking about it, which is a sign I guess that I should blog more often, not because anyone reads them, but just because writing this stuff down is useful for my own memory.

I don’t need your consent

Note: As of the 5th August there’s an update to this post, after the instagram posts, right at the bottom.

I’ve been taking photographs in public places (often called Street Photography) for around three years. I’m as surprised as anyone that I’ve discovered an interest in documentary, social, street, urban whatever you want to call it photography. I truly thought I’d take up photography and spend my time pointing expensive long lenses at wildlife, and expensive macro lenses at other kinds of wildlife. I even blogged about it here. I’m no good at it mind you, but I’m still putting in the effort and practice and hopefully over time I’ll improve. I don’t feel that I have a very artistic eye, and so a lot of my photography is workmanlike, technically okay quality (focus, exposure, framing) but not necessarily always very interesting.

I’ve been taking photographs in public places (often called Street Photography) for around three years. I’m as surprised as anyone that I’ve discovered an interest in documentary, social, street, urban whatever you want to call it photography. I truly thought I’d take up photography and spend my time pointing expensive long lenses at wildlife, and expensive macro lenses at other kinds of wildlife. I even blogged about it here. I’m no good at it mind you, but I’m still putting in the effort and practice and hopefully over time I’ll improve. I don’t feel that I have a very artistic eye, and so a lot of my photography is workmanlike, technically okay quality (focus, exposure, framing) but not necessarily always very interesting.

Anyway, that’s mostly an introduction. In the three or so years I’ve been doing it, I’ve not had any trouble. I even took photographs of armed police officers, and had some conversations with them, and never had any trouble. It can be daunting, pointing your camera directly at strangers in the street. Of course we don’t think twice about taking a photograph of friends or family and getting a few straggling strangers in the background, or taking snaps of attractions or tourist views, and again, catching a few strangers in the frame. It’s different though when you know you’re pointing your camera at someone you don’t know, and they don’t necessarily know you’re taking a picture.

I try and be socially aware. I avoid taking photographs of people I consider vulnerable, the definition of which is mine and mine alone. I work hard not to take photographs of people ‘just because they’re attractive’. I don’t take photographs for the most part of isolated children. I take a lot of photographs in Old Market Square, and there are often kids playing in the water and fountains in the summer months, and I am aware of that and it informs where I point my camera and what I shoot.

However, I also know my rights as a photographer in the UK (but I am not a lawyer, and this is not legal advice). They boil down to this – and I’m going to state them quite coldly. I don’t need your consent. If I’m in a public place, and you’re in a public place, then in general I don’t need permission to take your photograph, or a photograph of your children, or anyone elses children for that matter. There’s a right to privacy within UK law, and that means that in some situations a photograph could be inappropriate despite the notion of it being a public place. For example, photographing someone entering or leaving a family planning clinic could ultimately be an invasion of privacy. But, within the bounds of decency and privacy, I don’t need your permission. I do need your permission to use the images for ‘commercial’ purposes, but again, that’s actually a limited range of uses applied to advertising a product or service, or similar use. I can take photographs all day of people in the street and publish books full of them and never need a model release form.

So I’ve never had any trouble.

Until today.

The Nottingham Beach is on again this year. The council and am event company work together to turn the Old Market Square into the seaside. There’s sand, water, rides, arcade machines, fish and chips, donuts, slushies, ice cream, it’s great. The kids love it, families love it, and it’s always busy. This year is no exception. I went into the city today hoping it was going to be very sunny with heavy downpours. I definitely get my best shots when people are surprised by sudden rain and go running. Sadly for me it stayed dry, although I guess the families preferred it that way. I hadn’t taken any shots of the sand area because there weren’t any interesting compositions and it was mainly just families having a good time.

The Nottingham Beach is on again this year. The council and am event company work together to turn the Old Market Square into the seaside. There’s sand, water, rides, arcade machines, fish and chips, donuts, slushies, ice cream, it’s great. The kids love it, families love it, and it’s always busy. This year is no exception. I went into the city today hoping it was going to be very sunny with heavy downpours. I definitely get my best shots when people are surprised by sudden rain and go running. Sadly for me it stayed dry, although I guess the families preferred it that way. I hadn’t taken any shots of the sand area because there weren’t any interesting compositions and it was mainly just families having a good time.

I was speaking to Greté on Facebook messenger while eating a sandwich, telling her about the rides and the food stalls, and I said I’d grab her a few shots so she could see what the place was like. So I took some of the fish and chip stand, the donut stand, the slushy stall (including a security/event management guy, and the lady running the stall since that were standing in front of it). I turned, took a couple of the sandy beach, two of the water, and a couple of those inflatable ball things you can stand inside. I was, as ever, conscious of the kids, and so I took wide angle shots showing the whole area. I then wandered around a corner, decided not to take a shot of the surf machine (wasn’t running) and was about to leave, when I heard someone shout ‘oy’ behind me.

The guy from the slushy stall strode towards me, shouting, “You can’t take photographs here”. I told him I could because it was a public space. He switched immediately to, “You can’t take photographs of kids without their parent’s permission”. I said sorry again, but I could do exactly that, although I hadn’t been. By now he was beside me and made his first grab for my camera. I stayed calm, held my ground, and said that once again, I knew my rights, this was a public space and so I was within my rights to take photographs. We exchanged those views a couple more times, with him forcefully telling me I wasn’t allowed to take photographs of kids without their parent’s permission. He made at least one more grab for my camera during this period. After a couple of minutes, and me once again saying that I could, he said, “Let’s see what the police think then”? I said I was more than happy for them to be involved. I think that might have been the first moment where he wondered if he was on the right side of the conversation.

He picked up his radio, but before he could say anything, he caught the eye of an older member of staff who came over. The first guy explained what had happened, I explained that it was a public space and I was within my rights to take photographs. The first guy went off on his tirade about me taking pictures of the kids without permission, to which I said I didn’t need it but hadn’t been anyway. I then tried to explain four times why I was taking the pictures, that my wife had said she wanted to see what the place looked like. Each time I got three words into that, the first guy talked over me saying, “What are you, a nonce”? Eventually, I just held the gaze of the second guy, and he got the first guy to stop talking.

He picked up his radio, but before he could say anything, he caught the eye of an older member of staff who came over. The first guy explained what had happened, I explained that it was a public space and I was within my rights to take photographs. The first guy went off on his tirade about me taking pictures of the kids without permission, to which I said I didn’t need it but hadn’t been anyway. I then tried to explain four times why I was taking the pictures, that my wife had said she wanted to see what the place looked like. Each time I got three words into that, the first guy talked over me saying, “What are you, a nonce”? Eventually, I just held the gaze of the second guy, and he got the first guy to stop talking.

The second guy then asked if I would show him the photographs I’d taken. I know my rights, he can ask that, but he’s got no power to force me to do it. However, it made no sense not to comply unless I wanted this to escalate further which I didn’t. So I showed him the shots – about 10 of the Nottingham Beach, and then as we went further back doors, doorways, manhole covers, graffiti, you know, the normal kind of holiday snap. Eventually he said something, I can’t remember exactly, but it was clear he’d seen enough and wasn’t worried. The first guy was still unhappy, so I offered to delete the two images I’d taken with him in, I showed him me deleting them, and then I left.

My adrenaline was through the roof, and I was pretty fucking angry. There are a number of reasons for being angry. Firstly, 99% of the people in that location are taking photographs non-stop on their mobile phones. Themselves, their kids, other kids, other people, without a thought in the world, and then posting them straight to Facebook or Instagram or Twitter. I review every shot I take, and if I’m not comfortable with the content, or think that it paints people in a bad light, I don’t post it anywhere. People with mobile phones sometimes automatically post everything to social media without even a second glance. Secondly, and related to that, the only reason I got stopped is because my camera is large. It’s not a long lens focally, but it’s a physically big camera and lens. If I’d been using a smaller camera he wouldn’t have even blinked.

My adrenaline was through the roof, and I was pretty fucking angry. There are a number of reasons for being angry. Firstly, 99% of the people in that location are taking photographs non-stop on their mobile phones. Themselves, their kids, other kids, other people, without a thought in the world, and then posting them straight to Facebook or Instagram or Twitter. I review every shot I take, and if I’m not comfortable with the content, or think that it paints people in a bad light, I don’t post it anywhere. People with mobile phones sometimes automatically post everything to social media without even a second glance. Secondly, and related to that, the only reason I got stopped is because my camera is large. It’s not a long lens focally, but it’s a physically big camera and lens. If I’d been using a smaller camera he wouldn’t have even blinked.

Street photography is important. Even in an age where everyone has a camera with them, those cameras are increasingly turned towards the owners. Even if street photography isn’t important, even if my photographs are worthless artistically and historically, they’re still mine, and I still have the right to take them.

Amusingly, I had completely forgotten that at the start of last week I changed the shooting mode on my camera. My camera supports two cards, a CF and an SD. For a long time, I’ve been using the CF card and running into the SD card only when the first is full, to give me a buffer in case I’m taking a lot of shots. The SD cards are slower, so I don’t want to shoot to them constantly. However, last week, after watching yet another YouTube video with someone saying ‘my CF card died’, I switched to dual card mode, where the camera writes a RAW file to the CF card, and a JPG to the SD card. I had utterly forgotten this as I deleted the JPGs in front of the security guard. Leaving the RAW files intact on the CF card. Oh well.

Amusingly, I had completely forgotten that at the start of last week I changed the shooting mode on my camera. My camera supports two cards, a CF and an SD. For a long time, I’ve been using the CF card and running into the SD card only when the first is full, to give me a buffer in case I’m taking a lot of shots. The SD cards are slower, so I don’t want to shoot to them constantly. However, last week, after watching yet another YouTube video with someone saying ‘my CF card died’, I switched to dual card mode, where the camera writes a RAW file to the CF card, and a JPG to the SD card. I had utterly forgotten this as I deleted the JPGs in front of the security guard. Leaving the RAW files intact on the CF card. Oh well.

When I got home I did some digging, and I can find no reference to the Old Market Square Nottingham Beach not being public access. It’s possible I’m wrong, and that it’s designated as something else during the event. I can certainly imagine the ‘bar area’ counts as something special, since it has to be licensed, but I believe I’m in the right about the other areas. There’s unfettered access and no signage to suggest otherwise. I also went looking for photographs of the beach online, and there are plenty, all of them including plenty of kids in the shots – because of course, the beach is full of kids.

I don’t need your consent, but I do have empathy, and I behave in a socially responsible manner. But I’ll defend my right to take photographs in public.

For more information and advice about your rights – check out these links.

Lastly, here’s a few links to other photographs of The Nottingham Beach (none of these are mine). I’ve avoided including ones taken by parents and then posted publicly to Instagram with close up identifiable shots of their children and other people’s children.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BW4cARvnaP5/

https://www.instagram.com/p/BW2rsSXA0ZA/

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWzqN2alEV9/

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWnSR7UHXdu/

You get the idea.

Update (5th August) – since writing this blog post, I’ve been in touch via e-mail and on the phone with both the event organisers and the agency they use for the staff. In the first e-mail response from the agency which provides the staff, they lied about the interaction, making claims of events which didn’t happen and dismissing those that did. The conversation on the phone with the individual from the event organisers was more constructive, and I understand his position, when neither side can present evidence he’s not able to decide which is true. In a subsequent phone call from someone at the agency which provided the staff, it was clear that he’s going to back his staff, and while he apologised, he continued to use phrases like, “if what you described happened …”

Both of them insisted that they see a lot of suspect people taking photographs, and the police have warned them to be on the lookout. I don’t know how true either of those statements are, but I’m more than happy to be respectfully approached by concerned staff and members of the public. That’s a significantly different position from verbal abuse and potentially common assault.

I certainly won’t be spending any money at the event, and if you do go with anything larger than a smartphone, be prepared to justify your presence.

Night of the Zombie Healthcare Assistant – Days 6 and 7

This the 5th post in a series of posts about my accident and subsequent surgery and recovery. You can read the other posts at these links, days 1 & 2, day 3, day 4 and day 5. This post covers day 6, Saturday 27th August and day 7, Sunday 28th August. It’s been much harder to write than the previous set of posts.

Edit: So hard in fact, that it’s almost a year since my accident, and eight months since my last blog post (which was day 5 of this series). Half of this post was written in October 2016, the other half, written today, July 2017.

When I was discharged from hospital I had the story in the last post burning inside me. I was angry about how Alan and I had been treated, and was amazed at the behaviour of the staff, and so as I lay on the sofa at home, not able to sit at a computer or type, I knew I wanted to write something about that experience. I thought about it, thought about what I’d write and waited for the moment I could actually physically do it. I had intended to just write a single post about the night but realised early into the writing that I needed to tell the whole story of why I was there as well.

Telling the story of day 5 kept me writing, kept me putting down the words of the other days because I knew I wanted to tell that story – and once it was done, almost the instant I put the words down, it was a huge relief. Unfortunately, it was also so cathartic that I stopped having any drive to talk about the remaining days. Also, the remaining days don’t seem very interesting to me, where-as I knew there would be interest in day 5. However, I’m going to try and finish this up, and write at least three more posts. This one, one covering my discharge and one covering my recuperation at home. Wish me luck, and if you’re still reading these, thanks for going on this journey with me!

So, on to day 6, where I talk about opening my bowels …

Day 6

Shoulder dressing.

I’d survived the Night of the Zombie Healthcare Assistant but I wasn’t exactly well rested. It had been a night of morphine and pain and Alan’s singing. There was good news to come though – the Saturday morning shift were excellent nurses and healthcare assistants. I kept my mouth shut while they did a handover with the evening crew, but I gave the overnight folk a Paddington Bear Hard Stare.

Really early in the morning Alan got a visit from a doctor, and he was immediately on intravenous antibiotics. He was still restless early on during the day, but by the end of Saturday he was in much better spirits (he went through three bags of antibiotic liquid). During the day, the nurses also got Alan out of bed and into a chair, the first time he’d been out of bed since his accident. They were firm with him, because it was painful, but he felt the benefit in the end.

It required the use of a rotunda and several nurses because Alan couldn’t walk. It was an example of good nurses, doing something hard for both them and the patient, with the right level of engagement. Alan is 6 foot 2, moving him was no easy task. I think about twice a day while turning him, or moving him, or giving him his morning bath one of the nurses would comment on his height, and he would tell them he was 6 foot 2.

It was good being able to chat to Alan face to face across the ward with him sitting in a chair, instead of over my feet and over his feet. It was even better seeing him on the mend thanks to the antibiotics. I don’t think he remembered much of the previous day and night because he was essentially delirious during it, which is a blessing. He had a few stories and I was more than happy to listen to them, hopefully even just that little bit of engagement from someone made his days more bearable. He only had one visit while I was there, I think from grand-kids but I’m not entirely certain (I wasn’t trying not to pry) and he was much happier for it.

Edit: Everything from here is written in July 2017, and my already hazy memory is even worse, I’ll summarise everything except the main reason for writing this day, and it’s going to be all out of sequence.

The Good

The half cast I left the hospital with, but I was finally home.

I had a visit from occupational therapy. They were great. I think they were expecting me to be reluctant about living in a single room at home for my recovery. I was ecstatic at the prospect of getting out of hospital. We talked about being in a single room, being able to move from the sofa to a commode, I proved I could stand on one leg. They brought a wheelchair, with both directions controlled via rails on one wheel (because I could only use my right hand), but we agreed while it was doable, there wasn’t room in the house to actually go anywhere with it. In the end, Greté got me a loan chair from the Red Cross for use outside, hospital visits and the like. We didn’t use it much, but it was a life saver. The OT’s told me they would do a home visit, and that all happened in a bit of a whirlwind, I can’t thank them enough, that part of the whole process went really well. Essentially, I have them to thank for being discharged so quickly. Speaking of which, I had decided almost straight away that there was no chance I’d be discharged over the weekend, you can never find consultants, and Monday was a bank holiday. I had become resigned to not getting out of the place until Tuesday at the earliest. Given the events below, that was a pretty distressing thought for me. And then on Sunday morning they told me I was going home. I couldn’t believe it. The OT’s had got everything lined up in amazing time, a commode had been delivered, and they’d confirmed with the consultants that I could be discharged. I honestly didn’t really believe it for a while. Greté and an amazing bunch of friends rushed around to sort the house, moving furniture (a sofa out of the lounge to make room, stuff out of the dining room to make room for the new sofa, tables moved upstairs, and a load of other stuff). I’m eternally grateful to those people for pitching in when we most needed it. I was going home, and even now I’m emotional about it.

The rest of the good? I got home, I got better, I got back on my feet, I can walk almost as far as I used to be able to, and there are precious few things impacted by my arm mobility. It’s not 100%, but it’s enough to do what I need to do and it’s still slowly improving.

The Bad

My first cast, a couple of weeks later, lovely pink!

Saturday and Sunday weren’t all fun and games, sadly. Alan went downhill as the day wore on, and by evening he was in a lot of discomfort again. So little sleep the night before had left him extremely tired, and he basically nodded off into his food, and was ignored by the nursing staff. He was on limited liquid intake, but the tea lady didn’t know that so kept giving him full cups of tea even though he tried, and I tried, to tell her not to. The nursing staff then blamed Alan for the tea. He was too tired to understand, with the lack of sleep affecting his already bad hearing. It was a truly shocking display of a lack of care, and I’m appalled how little time experienced, qualified and motivated staff had.

My whole medication situation had been frustrating during my stay – including my regular drugs. I got so frustrated that I basically argued with a nurse when she tried to give me twice my regular Ramipril dose on Saturday evening. By Sunday morning, after a confirmation text with Greté, I realised she’d been right, because my dose had been increased only a few weeks prior, and my stress had resulted in me forgetting. I apologised to her the next morning. I don’t think she even remembered.

The Ugly

The shoulder wound.

If you have a weak stomach, turn away now.

One of the side effects of any general anaesthetic is constipation. Some people suffer worse than others, and it can be serious if not properly handled. A regular question from the nurses for both myself and Alan is whether we’d had a bowel movement. It was, in fact, a great topic of conversation between myself and Alan. As an aside, a few days after I got out, I rang the hospital to find out how Alan was. I couldn’t talk to him, and the nurse wouldn’t tell me without checking – since I wasn’t family. I said I just wanted to know how he was, she went and checked, and came back, and said, “Alan tells me, to tell you he’s fine, and he’s finally had a bowel movement”. I was so happy for him, because he was on the road to getting out and he still had his sense of humour.

Anyway, late on Saturday I thought I finally felt as if I needed a bowel movement. I wasn’t able to put any weight on one leg, I had my arm in a sling, and while close to the loo, there was no way I could get in there unaided. So, I asked the male nurse what my options were – he brought a commode on wheels. He wheeled me in to the bathroom, checked I was okay, and closed the door. I lifted my down, sat down and gave it my best shot.

Eventually, I noticed that my good foot was warm.

Because I was pissing straight onto the floor.

The commode didn’t fit over the loo properly, there was about a 3 inch gap between the hole in the commode and the front of the loo itself. As luck was have it, I wasn’t able to have a bowel movement anyway.

But let me tell you – that was a fucking embarrassing and humiliating experience, and conversation, when I called the nurse back in. He didn’t even really seem to register, he just wheeled me back to the bed, and then cleaned it up. I’m not sure if he was embarrassed, or just didn’t care. It certainly didn’t give me any confidence about going home and using the commode (as it happens, while I fucking hated using the commode at home, it worked, and I didn’t have to use it for long). I never did have a bowel movement in the hospital, which is probably good, because I dread to think where it would have ended up.

The Rest

A lovely green cast the second time around.

I got out on the Sunday. I spent a couple of months sleeping on the sofa, living in a single room, with Greté looking after me. I had a number of hospital visits, first to have the half cast taken off my leg, and replaced with a full cast, and then that was replaced again, as well as having my shoulder bandages removed. It was a long couple of months. Getting back to work wasn’t much fun either, due to a number of issues, but that’s all behind me. I won’t talk about the hospital transport experience for the first appointment – that was humiliating. We used the car after that with the wheel chair Greté had borrowed.

Physiotherapy has been worse than useless, and caused me some mental anguish, I’m not doing the exercises on my arm I should be, and I’ve got another checkup in a few days, since the year is nearly up, where the shoulder surgeon will review progress.

My foot is painful sometimes, but my walking gate is almost normal now – and they told me it can take a couple of years for the foot injury to fully recover, so I’m not too worried.

I started getting back out with the camera as soon as my foot could stand it, and I’ve done as much as possible as the months have gone on to keep my mobility up. My diabetes has suffered, and I’m not sure I’ll ever get back the control I had before the accident, but that could just be age and laziness as well.

The End

I wanted this post to be more amusing, more passionate, and include a lot more about Alan. I lost touch with him after that phone call, wrote him a card but when we tried to take it in he’d been discharged and they had no forward address. I hope he’s doing well and recovered from his hip fracture. But the passion for writing this has gone. Writing about that night on Day 5 was just so cathartic, that the rest seemed trivial, even pissing all over my own foot in a claustrophobic hospital toilet doesn’t seem bad when you compare it to the night of Day 5.

I want to thank again everyone who was there for me, and more importantly to me personally, everyone who was there for Greté during the whole time. Who’d think me breaking two parts of my body would have such long lasting effects, but it triggered further ill health for Greté mentally, and we’re probably still not really out of the period of adjustment after it.

Thanks for reading these – this unfinished post has been hanging over me for 8 or 9 months, and I hope that now it’s done I can get back to writing some more posts about happier times.

Night of the Zombie Healthcare Assistant – Day 5

And so here we are, 5 days into my story (the fourth post) but a long, long way from full recovery. I guess this is the pay-off post given the title, but I’ll continue writing articles after this one covering the rest of the process (I promise, I’ll condense them). This one though is a smörgåsbord of pain, failure, morphine, bodily fluids and wide eyed terror. Welcome aboard, I hope the journey was worth it.

NB: Hardly any pictures in this post, I wasn’t in much condition to lift the phone up.

NB: This is a long, long, long post with a lot of text. Sorry.

Also NB: Day 1 & 2 here, day 3 here, day 4 here.

Day 5

Early start, I don’t look impressed.

This post might jump around a bit, and first off, I wanted to talk about Alan. Alan had done nothing wrong other than fall down some stairs. He’d done nothing wrong other than make it into his 70’s with a mind as sharp as a tack. He deserved respect and dignity, and more than that, he deserved the best standard of care that you can find in the world. What Alan got was a crap shoot where one minute he was being dealt with sensitively by someone who truly cared and the next he was being managed like a problematic child you wish you’d never had. It all depended entirely on which nurse or healthcare assistant he got at the time. We all experienced this in the ward, some of the staff were fantastic, and some were pretty rubbish and ineffective, but in some ways, we were able to fend for ourselves a little more than Alan.

He’d been lying flat for a few days by the time I was admitted, and along with incessant hiccups (which were sadly a source of amusement for most of the staff) he was beginning to get a bit wheezy (day 4). I watched as Alan basically picked up a chest infection in slow motion (day 5). Nurses could tell it was coming. Healthcare assistants commented on it. Yet it felt like the plan was wait until it took hold and then pump Alan full of antibiotics to get rid of it again (day 6). It was like watching paint run down a wall and only when it spilled onto the floor take action mopping it up. Could they have prevented the infection, would antibiotics a day earlier have held off the worst of it? I don’t know, but it was tragic watching it take hold (you’ll see, later).

Alan told everyone who dealt with him that he was deaf in one ear, and hard of hearing in the other. The best of the staff remembered and stood on his good side and spoke loudly and clearly. The worst of the staff ignored his hearing and just talked to him like a child when he failed to hear what they said. I started saying ‘he’s deaf in that ear’ when Alan struggled to hear what they were saying. I was in a bed, on the other side of the ward, and I could hold a fucking conversation with Alan, deaf and hard of hearing, better than some of the staff did while standing next to his head. He wasn’t stupid, he wasn’t tired, he was just hard of hearing. He deserved to be spoken to like an intelligent human being, not like a baby.

There were three shift rotations a day for the nurses and healthcare assistants, and during each rotation the new and old groups would do a round discussing all the patients. That was the handover, and it relied on short conversations, the memories of the people involved, whatever notes had been written into our folders and the words written above our beds on the white boards. It’s always great to be talked about as if you’re not there, I often chipped in during their discussions of me, but not once did any of them say ‘Alan is a bit deaf, stand on his right side’. I watched one set of nurses consult with a doctor when Alan was deteriorating, and they limited his water intake to 1 litre a day. But they didn’t write it clearly above his head, nor did they explain to Alan why. So when the tea lady came around for the rest of that day, she quite happily re-filled Alan’s jug and gave him full cups of tea. Later that day, the nurse complained at Alan about this. It wasn’t fucking Alan’s fault – he’s a patient, he’s not meant to be in charge of his own care. The communication between the staff was just terrible. Eventually one of the nurses told the lady who did the tea about the fluid limit, but the next day, it was a different tea lady … and so Alan got too much fluid again. Eventually, myself and Alan had to keep reminding the people serving him water that he wasn’t allowed it.

Friday morning had arrived, I woke up early having had a pretty fitful night. I’d used up a few more cardboard urine bottles overnight, but the feeling had come back in my lower body and I was able to wiggle the toes in my left foot. While I’d been ignorant of the seriousness of my foot injury, and had been wearing the moon-boot, I’d been able to hobble around quite quickly. Now though I was in a light-weight cast which I wasn’t allowed to bear any weight on, in any way. I couldn’t hop because my left arm was too painful, so I was reduced to pivoting between the bed and the chair next to it if I wanted to move.

Nurses arrived with a fresh gown and a fresh pair of paper pants, along with a bowl of hot water, some more antiseptic scrub and some towels. They left me to get cleaned, saying if I needed help just to buzz with the alarm. That was the most painful washing experience in my life. My left arm was still almost entirely immobile and very swollen. I couldn’t bear even the weight of my own forearm and I couldn’t voluntarily move the arm more than 1cm away from my body. Even getting the gown off was extremely difficult and painful, but I managed. I changed my paper pants, washed as much of my arm as I could in preparation for the surgery and then got the gown back on (but not done up). I buzzed for the nurse, and waited.

And waited.

So I buzzed again.

And waited.

After about 20 minutes and my 6th buzz, the nurse arrived, irritated. Luckily, I hadn’t been choking to death, or hadn’t fallen to the floor, or hadn’t been suffering from any breathing issues or actually anything serious. I was just in pain, unable to get dressed, unable to walk, sitting on a bed waiting for someone to come and help me.

We got the gown tied up and then the nurse tried to put the foam sling back on my arm. She failed, getting the strap in the wrong place, despite me having explained how it needed to go. So I explained again how it needed to go over my shoulder, and she tried again, and failed. Both attempts were excruciating painful. I told her, rather angrily, that I’d sort it out myself thank you very much and she cleared away the water and towels and left me to it. The gent with the motorcycle injury looked over and said, “She’s rubbish”. And she was. I got to know her and her shift quite well over the small number of days I was there, and she was indeed, rubbish. She didn’t communicate, she didn’t listen, she didn’t care and she turned up at her own pace.

I got into trouble once on Facebook when I said something like 20% of people are shit. That includes hospital staff, the police, the army, the clergy, bin men, gravediggers, chefs, teachers, shop keepers, etc. Someone told me that people in the NHS deserve our respect. It’s true, they do. But equally, people are crap. Great people have crap days, and some people are crap all the time. Some people start out great and then get worse over time. Some people are great on day one and great on the day they retire. But the truth is, people are fallible, they have shit days due to regular issues we all suffer. When I have a bad day and go to work, the worst that happens is I write a snotty e-mail and have to apologise for it later. If you work as a nurse and you take your frustrations or stress in to work with you – people can suffer. I wouldn’t ask anyone to do it – I have the utmost respect for anyone that does. There are more good people than bad, more good people in the NHS than bad, but that doesn’t detract from the truth. Some people are rubbish and shouldn’t work in a role which requires them to help people.

This nurse was one of them, or she needed a holiday, or she needed more support from her own management, or something, but whatever the problem was, it impacted my health, and the health of the other people in that ward.

And, she wasn’t even the worst health care professional I was going to experience that day. That was to come much later.

When the nurse with the drug trolley came around that morning, I still wasn’t listed for any drugs, but I explained how much pain I was in and she gave me some codeine after much pleading on my part that paracetamol really wasn’t going to cut it. Then I got a visit from a surgeon. She wasn’t the lead surgeon or consultant doing my shoulder, but she’d come to do the pre-surgery assessment. She asked me how I was feeling, and I was pretty angry at that stage. I explained I was in pain. She asked if I’d been offered any pain relief and I explained I’d pretty much had to beg for codeine. She asked why I hadn’t had any morphine and I told her I hadn’t exactly been given a list of what I was allowed to ask for.

At which point she stood up, and said to the nurse team which were currently doing hand-overs, “Mr Evans doesn’t seem to be happy with his pain relief”. After which, I was fitted pretty quickly for subcut morphine (morphine administered via a subcutaneous line). Hilariously, the dose of morphine I got was delivered to me as I was lying on the bed on my way for a shoulder surgery and a general anaesthetic (GA) but you can’t have everything.

You have to consent to surgery, and they’re very serious about it. Before I got the morphine, we did that little dance with the surgeon explaining the risks and me trying to explain I’d already consented to shoulder surgery on Wednesday during my first appointment with the fracture clinic. But no one could find that paper work so we had to go through it all again. I got a visit from a new anaesthetist, and we discussed options, but given the location of the surgery and the intrusive nature, the only real option was general anaesthetic for this one. Then I was onto the trolley and getting some morphine. I did ask if there was any point and if it would interfere with the GA, but was pretty much dismissed by the nurse administering the dose.

I waved to Alan as I was pushed out of the ward and down to theatre. It was 9:42am and my day had already been a bit challenging.

I texted Greté around 4pm when I woke up, back in the bed. My arm was back in the sling, the only difference being the presence of some pretty big wound dressings. The surgeon I saw that morning would be the last time I spoke to a consultant or surgeon until after I was discharged. At no point did anyone come and tell me if either surgery had gone to plan or had issues, at no point did anyone tell me how to manage either of my injuries. I did, in frustration, explain that to one nurse and the next morning (I told you this would jump around) the on-call doctor came to speak to me, but all she could offer me was “there aren’t any comments on your notes, so I think it all went okay”. Come on NHS, I’m the patient, where’s the communication?

Anyway, I woke up, I was still groggy, Greté and her mum visited me. Over the days I was in, Simes and Sarah visited as well, but I’m ashamed to say I can’t remember on what days they visited. I’m grateful for their visits, but I just can’t piece together when they were! I stumbled through a conversation with Greté but I was clearly still recovering from the GA.

At some point during this day, I had a visit from the clinical pharmacist and we got my medication sorted out. I was prescribed codeine, paracetamol and ibuprofen, and my own diabetic medication was documented so I could use those as necessary. I’d had a couple of visits from the nurse with the drug trolley and one of the questions they and the healthcare assistants ask while doing hourly observations is, are you in pain and can you rate it from 1 to 3. They use 1, 2 and 3 in Derby because they found with 1-10 most people would just pick 1, 5 or 10 anyway. Mostly I responded 1 or 2.

A bourbon biscuit!

Greté left, I had some food and dozed for a bit.

Then around 8 or 9pm Alan started having trouble. He was clearly running a fever and was beginning to get very confused. He hadn’t been diagnosed with his chest infection at this stage, and wasn’t on antibiotics. Twice I watched him try and get out of bed, thinking it was time to go home. It was heart breaking. We’d had the evening nurse shift change and had a male nurse, a female healthcare assistant and another member of staff (not sure if she was a nurse or an HCA). I’d never see any of them before.

Alan was considered a high risk patient. He needed the compression on his feet, and he needed to be turned a couple of times a day and he was on hourly observations. I’d just come out of surgery on GA, and needed hourly observations. I was also in an increasing amount of pain.

Between 8pm and 11pm, I noticed the HCA walk into the ward a few times and stand in the middle, and then look confused and walk back out. She kept looking at a piece of paper in her hand, but would then simply leave the ward. Alan was restless, trying to get out of bed. My pain was increasing but I was still very groggy.

At around 11pm I watched the HCA, and she looked stoned; I’m sure she wasn’t, but she looked it. Maybe stoned, or in shock, or suffering from PTSD, or lost, or she could have been a zombie. Whatever it was, she was clearly out of her depth in a major way. Neither myself nor Alan had had any observations done for over 3 hours, no one had asked me about my pain, Alan had tried to get out of bed twice. He was singing, talking, thrashing and clearly distressed. I was starting to breath heavily to try and deal with the pain in my arm.

The Zombie HCA walked in, looked at her bit of paper, hung around, and then left.

I think I called out saying I needed something for the pain and she mumbled something.

A while later, I was hyper-ventilating and groaning involuntarily.

Alan was singing.

Zombie HCA walked in and straight out.

I started sobbing.

Alan sounded like he was coughing up a lung.

Eventually the male nurse came in. I don’t really remember much about the conversation, but he was irritated at the Zombie HCA, he was irritated at me, he wasn’t happy that I wanted some pain relief, but eventually, after another 50 minutes, he came back with some subcut morphine. I’d been in pain from 8pm, in serious pain from 10pm and in almost unbearable pain from 11pm, but around 12:30am I finally got some pain relief.

I say relief, but by them it was too late. Essentially, whatever they used to block the pain as part of the GA wore off in one go between 10pm and 11pm, so I went from being uncomfortable, to being in all the pain having your arm cut open and metal plates screwed into the bone can induce in the space of 60 minutes. The morphine just took the edge off and made me dozy, it didn’t kill the pain. Not long after this, the HCA spoke to me for the first time all evening, she said, “Can you rate your pain level between 1-3?”. I asked her if she was fucking joking, given she’d just watched me go from normal to sobbing in the space of an hour and beg for morphine, but she didn’t really show any signs of understanding what I was saying. I told the male nurse that “I didn’t trust the other nurses”, and he very angrily pointed out they weren’t nurses, they were healthcare assistants. I guess he was having a bad day.

I dozed in and out of sleep for a while, and when I woke up in pain, I buzzed and got more morphine. That happened another couple of times overnight, each time I’d wake up, buzz, and get more morphine.

Finally the night of the zombie healthcare assistant was over, and day 6 (Saturday) had begun.

Before day 6 however, here’s a section of other stuff that happened on day 5, but which I can’t place in the timeline because it’s all so fuzzy.

- During one of the drug rounds, after my surgery, a nurse pulled out a large needle and said ‘I need to inject this into your stomach’. It was pretty abrupt, and I said, ‘Why?’ She just said, ‘I need to’. So I told her no. I wasn’t prepared to accept some random medication that she couldn’t explain to me. She looked a bit confused but just left. Here’s a top tip, if you want patients to take medication, then you should explain to them what it is. I know that not all people are the same, some don’t care, some don’t understand, but some are intelligent, articulate, interested and aware, and when you have one of those patients you really need to do more than say ‘I am going to stick this in you’. Tune in on day 6 to see if I ever accept my heparin or heparin equivalent.

- Despite not being nil by mouth any more, they left that phrase written on my whiteboard and I had to explain it away every time the tea lady came by.

- While Zombie Healthcare Assistant was failing to do her observations properly (she did eventually take some, but she wrote them up wrongly on the system, mixing up the numbers) both the male nurse and the other female member of staff had conversations with her, explaining she was screwing up and trying to get her to correct the issues. But it didn’t help. I didn’t get any proper observations until the next shift change, and Alan was pretty much ignored all night. I assume the ward was understaffed, and I hope Zombie HCA gets the help she needs in whatever form it takes, but someone needs to manage their staff better.

- There had been a trainee nurse on the ward earlier – she was doing the HCA role. She was the only one who actually wrote everything in the folders, and she was constantly aghast at how little information there was. She took care of Alan before the shift change to Zombie HCA.

- The next day, the regular nurses complained amongst themselves at how much the trainee nurse had done. They were pissed off that she’d done lots of nurse stuff, not just HCA stuff, even though she was supposed to be doing HCA training. I think they were mostly pissed off that she made them look bad. Which of course, they were. I don’t know the relationship between nurses and HCAs or how the training works, or what role everyone was doing. I just know she was a nurse in some capacity, but was only covering, or learning, or supposed to be doing the HCA role in that ward, but because she saw holes in the care of the patients she just covered where she could and I appreciate that.

- Alan finally got some sleep, although he spent much of it mumbling and unhappy.

Night of the Zombie Healthcare Assistant – Day 4

Welcome to day 4, being the third post in a series of posts about my recent injury and recovery. This post contains bodily fluids, pictures of cannula and a lack of dignity. You can read part 1 here and part 2 here. They don’t contain any bodily fluids.

Day 4

Post-surgery cast and bandage.

We never got a chance to call the trauma nurse on the morning of Thursday 25th August to check if I was on any surgery lists, because she rang us first. The shoulder specialist had found his foot specialist the day before, and I had a serious lisfranc fracture of the foot – which needed urgent surgery and fixation (again, plates). I really should not have been putting any weight on it all, and the misdiagnosis in Carlisle had put my ability to ever walk properly at risk. Untreated lisfranc injuries can result in instability of the foot and serious issues with mobility. So I was being admitted at 11am, and despite expecting to be going in for shoulder surgery – I was going for foot surgery at round 2pm. We’d prepared a little overnight stay bag the night before when we got home so we were ready to go when the call arrived but it was still pretty fucking scary. I’ve had a broken arm (in my teens) and I knew I could get through the day only being able to use one of them, but foot surgery inevitably meant being off my feet for some time. I had no idea how long for. Also, with both the arm and foot injury being on the left side, I knew I wasn’t going to be using a crutch to get around – it was starting to look a little bleak.

We headed in, found our way to Ward 311 and on Thursday 25th, I’d gone from falling over playing tennis to being hospitalised four days later.

It’s around this point that my dignity became a victim of necessity. It’s also around this point that I started taking a lot more codeine a lot more regularly – and as a result, my memory is shit. All of the things I’m going to write about happened, but lets say that the order in which they took place or the exact sequence is more fluid.

Look how pretty it is.

Admission was pretty swift, they had the details from the previous day and the team were very efficient. With the surgery deadline in place, there wasn’t much time to get used to my new surroundings. I had to have conversations with the anaesthetist, the surgeon and the rest of the team. Before all of that though, I had to get ready. And by getting ready, I mean I had to shed my dignity. If hospital gowns are the worst invention of the modern age, then paper surgery pants are the worst invention of any age. Greté helped me get changed into both gown and pants, after washing down my leg with hibiscrub (or something similar), and I lay back in the hospital bed, feeling a bit like a turkey ready for basting. Do you know how easy it is for pubic hair to get trapped in paper underwear? Very easy.

I’ve only had surgery as an adult once, and I found that the person who seemed to care most about my well-being during the whole process was the anaesthetist. That was matched this time (although the surgeon was nice, to be fair). I had a long conversation about the style of anaesthetic I wanted. On offer were full general or, essentially, a spinal injection which would kill any sensation from below the waist and an injection freezing my foot in place. I never realised that general anaesthetics don’t come with any pain relief as such, where-as the other option was all about the lack of pain. However, if I went for the spinal injection, I’d be conscious for the operation – and I’d get something to help me relax without putting me to sleep. The anaesthetist asked which one I would prefer – I think I said, well, I’ll defer to you given it’s your job. He was insistent that I choose though – which I still find weird. In the end, I opted for the spinal injection because I quite liked the idea of being awake during the surgery. It was an excellent decision as my shoulder surgery later would prove. It wasn’t until much later that I realised the reason anaesthetists care so much, is because they’re basically holding your life in their hands, and in most surgeries, have more control over your well-being than the surgeon or anyone else in the theatre. If they fuck up, you don’t wake up.

The surgeon then paid a visit – and explained for the first time what the foot injury was and how it showed up on the x-rays. He also said that the bruising on the bottom of my foot was a classic symptom of fractures, if your foot bruises like that, it’s almost certainly broken. He explained the surgery, and drew three marks on my leg and foot. A massive arrow on my left calf, a dotted line on my foot where he said he was going to make his incision, and then another line on the inside of my foot with a question mark, because he wasn’t sure if he’d need two incisions or not. I finally got to wash those marks off my leg on the 18th of October, 54 days later. I spent some of those 54 days wondering if the ink was toxic when absorbed by the skin.

The surgeon also tossed in a throw away comment, that after the plate goes in, sometimes they take it back out after the swelling goes down, a couple of years down the line. Yep, two years of swelling around the plate.

Post-surgery selfie, complete with oxygen line.

What didn’t happen during all these conversations, was a proper discussion with the clinical pharmacist or anyone about medication or pain relief. Likely because I was being admitted quite late and going straight to surgery – but it would prove frustrating later on.

Eventually it was time to head out – and I hopped across onto the surgery trolley and told Greté to go home rather than wait since we didn’t know how long it would take. Off I went, paper pants and all toward the operating theatre. I had another conversation with the anaesthetist, we reviewed all the questions again about loose teeth, and then it was time for the injections. Leaning forward was pretty painful (see: fractured humerus) but once the various cocktails were in me it was a lot easier. I was in surgery and looking up at some bright lights. My memory of the surgery is strange. Time was really compressed, and I must have been dozing on and off, but I do remember talking to the surgeon and other people in the room. I remember seeing an x-ray of my foot with the plate and pins in it. I listened to the surgeon discuss where to put the next pins and how to lock the plate in place. I never felt a thing.

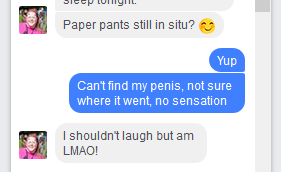

I woke up back in the ward, in bed, thankfully with my paper pants still in place. I could not feel my legs, or my back, but my leg had a half cast on it and a lot of bandage, so I knew something had happened. Luckily it was the correct leg as well! I’m piecing a lot of the rest of the day through a mixture of SMS and Facebook messages. Thanks to technology, I never felt far from Greté and friends, and most of the photographs in this post I took to send to Greté to let her know I was okay. I woke up around 7pm and texted Greté as soon as I could reach my phone. There wasn’t much point her coming back in that night so we just spent the time talking on SMS or FB. This is my favourite part of the whole conversation, Greté’s text is in grey, mine is blue.

Facebook messenger chat

I hope you appreciate that.

Flapping cannula.

So far, other than some confusion early on, the experience with Derby hospital had been pretty good. I can’t fault the consultant, the anaesthetist or the admission team. However, it was all about to start going downhill. I’d not eaten anything or had anything to drink since midnight and it was now 7pm, long after they serve evening meals. A lovely nurse ((note that I refer to a lot of staff as nurses, they may have specific roles and names, but I don’t know them)) checked with me and asked if I was hungry and wanted a sandwich. She brought two sandwiches back with a drink, and said I looked like I had an appetite. I was then informed that it would be nil by mouth again from midnight, because I was going in for shoulder surgery the following morning, at 10am.

I had a chance for the first time to get to know the other patients in the small ward I was in. Alan was in the bed opposite mine. Alan was in his 70’s, deaf in one ear but mentally sharp as a tack. He wasn’t from Nottingham or Derby, but had fallen down some marble stairs in a building somewhere in the region and broken his hip in three places. He was pretty immobile in the bed, had been in for a few days and had some kind of air-powered compression slippers on to keep the blood flowing in his legs. There was a gent on my far right who’d been in a motorcycle accident, broken both arms quite badly. He’d already been in surgery a few times, metalwork sticking out of his arms. His legs worked though so he spent a lot of time out of the room walking around. In between them was another guy, who I didn’t get to know, he was pretty much asleep and then discharged the next morning.

I had a bit of a chat with Alan which wasn’t easy, we were both drugged up and he was half deaf, but at least it was some conversation. The pain in my arm was getting worse, I hadn’t had any pain killers since the night before but I checked with the healthcare assistant (HCA) while she was doing my observations and she said the nurse would be doing her rounds with the drug cart in a little while. I also mentioned that my cannula appeared to be coming loose, but she didn’t seem very worried. Eventually the nurse with the drug trolley arrived, and we spoke about pain relief.

“There’s nothing down next to your name, I can give you some paracetamol.”

I was a bit frustrated by that. I explained calmly that I was in quite a bit of pain and really could do with something stronger than paracetamol. It turns out that because I was admitted and moved into surgery so quickly, I hadn’t had the review that happens when they work out what drugs you’re going to be prescribed. I told her I had a bag full of ibuprofen, codeine and paracetamol all prescribed to me the day before by the consultant. She said, “you’re not supposed to take your own tablets, but if I don’t see you taken them ….”

So I took them. Along with my diabetic medication.

While I was calming down from that (and enduring ‘hourly observations’) I noticed that Alan’s pressured foot things weren’t on his feet. I was just about to mention it to someone when one of the nurses / HCA’s noticed and replaced them, making concerned sounds about how long they’d been left off for.

I finished the day off with a massive wee; into two cardboard urine receptacles. I’d taken on board a lot of fluids during the surgery, and despite not having anything to drink since the previous night, I’d also not been to the loo since around 11am, so there was plenty of water to get rid of. When the nurse came to collect the used bottle, I had to let them know they were both full – I don’t think she believed me initially, but she took them both and returned with two empty ones. That would be a pattern for the next day or so, where I think I passed a volume of liquid equal to Loch Ness. I can’t quite describe the subtle terror of lying in a bed, not able to feel your own legs or find your own penis by touch, weeing into a carboard bottle which is resting on the bed, trying to work out if you’re holding it at the right angle so that it doesn’t just spill out of the top.

I finished the day off with a massive wee; into two cardboard urine receptacles. I’d taken on board a lot of fluids during the surgery, and despite not having anything to drink since the previous night, I’d also not been to the loo since around 11am, so there was plenty of water to get rid of. When the nurse came to collect the used bottle, I had to let them know they were both full – I don’t think she believed me initially, but she took them both and returned with two empty ones. That would be a pattern for the next day or so, where I think I passed a volume of liquid equal to Loch Ness. I can’t quite describe the subtle terror of lying in a bed, not able to feel your own legs or find your own penis by touch, weeing into a carboard bottle which is resting on the bed, trying to work out if you’re holding it at the right angle so that it doesn’t just spill out of the top.

Luckily for everyone concerned, I have great pelvic floor control.

Despite several queries and reminders no one really bothered fixing my cannula, and despite the fact that my arm was seriously painful I eventually just nodded off, ready for day 5. You’ll be pleased to know that day 5 is finally the Night of the Zombie Healthcare Assistant.

Night of the Zombie Healthcare Assistant – Day 3

This is the second post in a series of posts covering my injury and subsequent recovery. You can check out the first part here. This one’s not to bad, but if you don’t like to hear about bodily fluids, you probably want to skip the next one (which I’ve not written yet, but I already know how it goes), and to be fair, most of the ones after that one too.

Day 3

Bruise starting to develop nicely.

After an uncomfortable night, muted by a lot of codeine, I was up and hobbling around on Wednesday 24th August ready for my appointment at the fracture clinic. I prefer the Royal Derby Hospital over Nottingham (we live in a place that lets us choose) for various reasons – so we squeezed me back into the car, padding in place, and got there early. I’m always early. Usually, very early. I was once an entire day early for a medical appointment (I had to go back the next day). Luckily the fracture clinic isn’t far from the main car park but despite my protests, Greté made sure I was in a wheelchair rather than allowing me to walk. I’m grateful now, but at the time my pride was a little fractured too.

The fracture clinic system at the hospital is a bit free-form. You arrive in the main reception, and sit for a bit, then someone calls your name and you go through to an examination room, and then you wait as long as it takes for the consultant to come and see you. The nurses seem to be just as confused about what is going on as everyone else, and it felt very chaotic. However we’ve been a few times now and I think what it means is that, because people need x-rays or casts and other procedures during the whole appointment, they can basically manage the list of people without being overly rigid. If your appointment time is 2pm but you arrive at 1pm, you’re likely to be seen before 2pm, because there’s a gap while a brace of more mature patients are having casts put on, or whatever. So we were in an examination room pretty quickly, but it took more than half an hour for a consultant to then come and check me over.

Lovely bruise on the base of my left foot.

To add to the confusion, we weren’t coming in via a normal route. Normally, you fall over or suffer a trauma, and either go straight to the clinic or get referred immediately by A&E. We had kind of self-referred a couple of days after the accident, so they had previous notes to look at from another hospital, but no one had done the normal trauma / fracture questionnaires that Derby usually do.

Lastly, as a patient, you tend to get told nothing until the last minute. We’d not been to the fracture clinic before and didn’t really know what to expect, so the waiting was even harder (with or without pain) and people would come, ask questions, and leave and we’d not be sure what that all meant.

However, eventually a consultant came to see me and we went through a few basic questions – and then were immediately sent off to x-ray. X-raying fractured limbs is painful, because you invariably have to get them into positions they do not want to go into. I was still blithely and happily standing on my foot when required, but moving my arm around was agony. X-rays done we wheeled back to the reception and went straight back into an examination room. What followed was one of the most amusing and yet uncomfortable hospital interviews ever.

More bruising