In part one of this set of posts, I covered using SSH tunnelling to access a service on a server, from a particular machine that can SSH to the target server, but not access the service directly (due to firewalls or sensible security reasons). In this post, I’ll cover a three computer scenario.

Example 2 – three computers – can’t access third server directly

This situation covers a few different scenarios. Perhaps you can SSH to a server in a DMZ (i.e. firewalled from all sides), and from there you can SSH to another server, or perhaps access a website on another server, but you can’t get directly to that server from your computer (you always have to use the middle hop). Maybe you want to interrogate a web management GUI on a network switch which is connected to a network you’re not on, but you can SSH to a machine on the same network. There are plenty of reasons why you might want to get a a specific service, on Server 2, which you can’t access directly, but you can access from Server 1, which in turn you can SSH to from your local computer.

The process is identical to the steps followed in the first example, with the only significant difference being the details in the SSH command. So let’s invent a couple of different scenarios.

Scenario 1 – remote MySQL access

In this example, your web server (www.example.net) provides web (port 80) and ssh (port 22) access to the outside world, so you can SSH to it. In turn you have another server on the same network as your web server (mysql.example.net) which handles your MySQL database. Because your sysadmin is sensible, mysql.example.net is behind a software firewall which blocks all remote access except for MySQL and SSH access from www.example.net.

So your workstation can’t SSH to mysql.example.net and hence you can’t use the simple example in the previous article. You can SSH to www.example.net but you can’t run the GUI up on that computer. So you need a way to tunnel through to the third machine. I’ll show you the command first, and it will hopefully be obvious what’s going on.

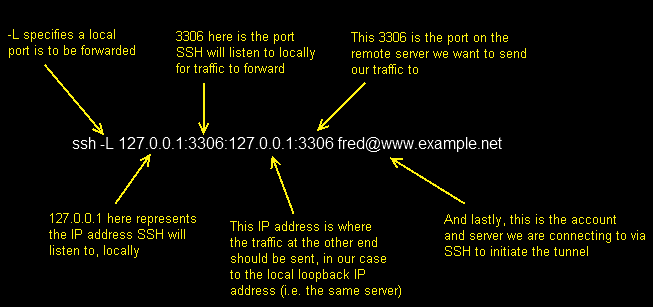

ssh -L 127.0.0.1:3306:mysql.example.net:3306 fred@www.example.net

So as before, we open the tunnel by connecting to www.example.net as fred via SSH. The tunnel we are creating starts on our local machine (127.0.0.1) on port 3306. But this time, at the other end, traffic ejected from the tunnel is aimed at port 3306 on the machine mysq.example.net. So rather than routing the traffic back into the machine we’d connected to via SSH, the SSH tunnel connects our local port, with the second server’s port using the middle server as a hop. There’s nothing naughty going on here. SSH is simply creating an outbound connection from www.example.net to mysql.example.net port 3306, and pushing into that connection traffic it is collecting from your local machine.

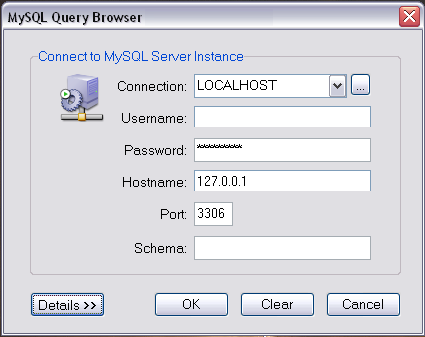

Once the tunnel is in place, you would start up the MySQL GUI exactly the same as previously, filling 127.0.0.1 as the ‘server’, and the correct credentials as held by mysql.example.net. SSH will pick up the traffic, encrypt it, pass it over port 22 to www.example.net, un-encrypt it, and then pass it to port 3306 on mysql.example.net, and do the same in reverse.

The only difference between this and the example in part one, is the destination for our tunnel. Rather than telling SSH to talk back to the local address on the server we connect to, we simply tell it which server we want to connect to elsewhere in the network. It’s no more complex than that.

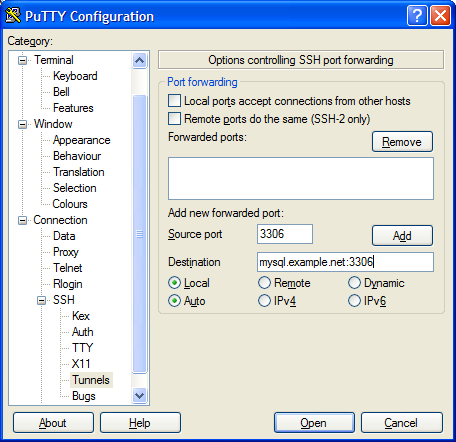

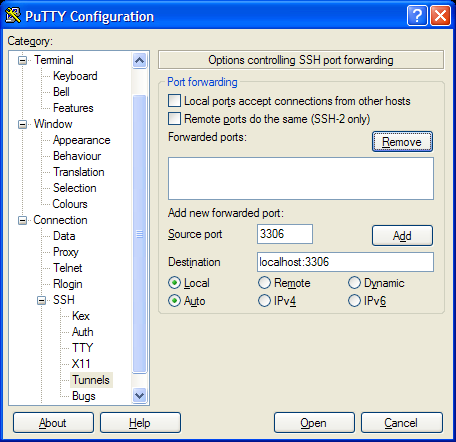

Here’s the setup for PuTTY.

Scenario 2 – network switch GUI

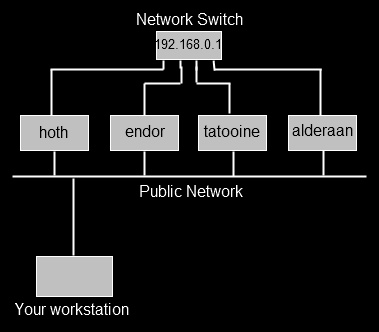

Maybe you support a set of servers which you can SSH to, but which also have their own private network running from a switch that itself isn’t connected to the public network. One day you need to use the web GUI on the switch (perhaps management have asked for a screenshot and they don’t understand why you sent them an ssh log file first time around) which runs over port 80.

So, we can ssh as user fred to say, the server endor using ssh fred@endor. We can’t connect to our network switch (192.168.0.1) from our own workstation, but we can from endor. What we need to do is create a tunnel from our machine, which goes to endor, and then from endor into port 80 on the switch. This time, we won’t use port 80 on our local machine (maybe we’re already running a local web server on port 80), we’ll use port 8000. The command therefore is this,

ssh -L 127.0.0.1:8000:192.168.0.1:80 fred@endor

So, make SSH listen locally (127.0.0.1) on port 8000, anything it sees on that port should be sent over port 22 to endor, and from there, to port 80 on 192.168.0.1. SSH will listen for return traffic and do the reverse operation.

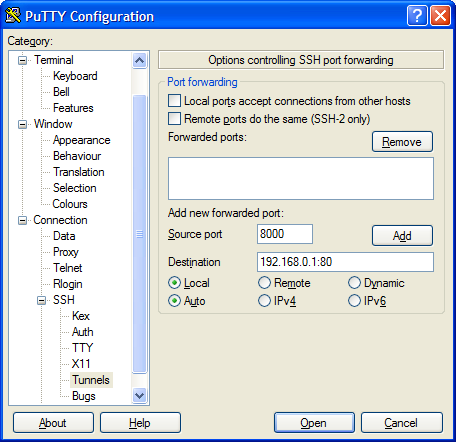

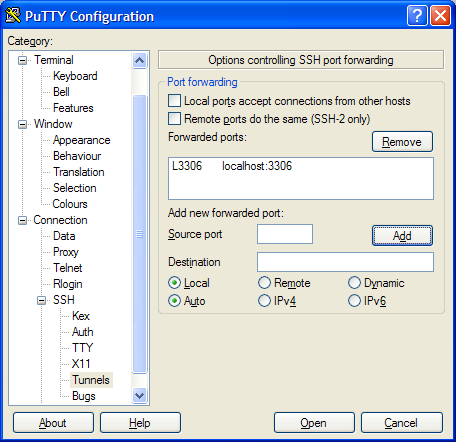

This is how that looks in PuTTY.

Once we’ve connected to endor, and the tunnel is in place, we can start a web browser on our own local machine, and tell it to go to the url,

http://127.0.0.1:8000

At that point, SSH will see the traffic and send it to the network switch, which responds, and the tunnel is in place.

Once again, this process works for all simple network protocols such as POP3, SMTP, etc.